Editor’s Note: NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index, a leader tracking Mexico natural gas market reform, is offering the following column by Eduardo Prud’homme as part of a regular series on understanding this process.

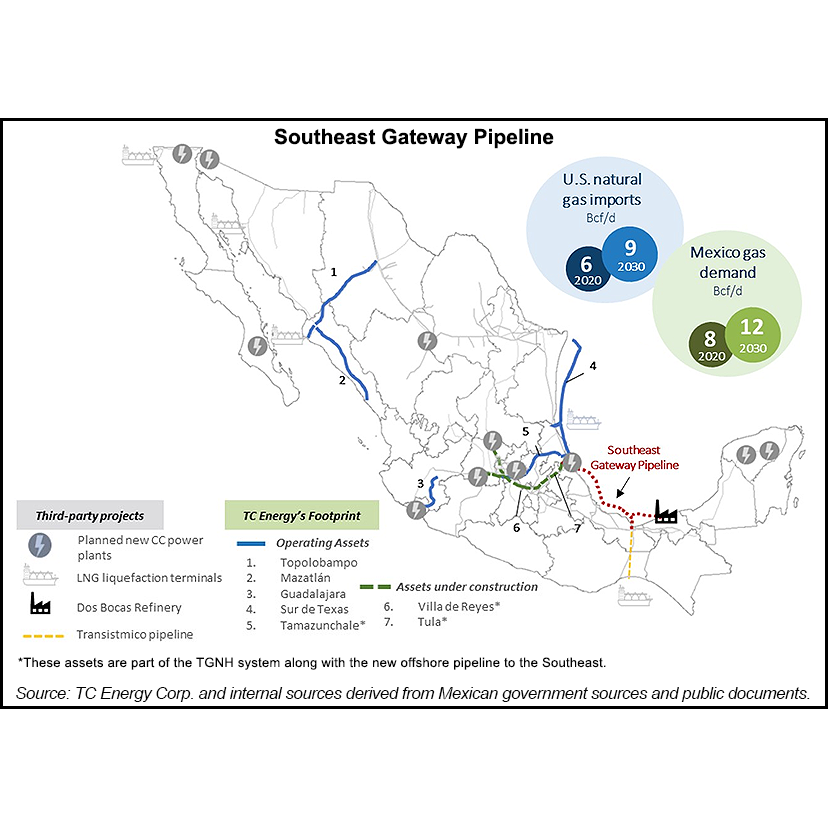

It’s impossible to deny the positive aspects of the 1.3 Bcf/d Southeast Gateway Pipeline project announced by TC Energía in the first week of August. At a time when the Yucatán Peninsula faces great vulnerability in its electrical system, caused largely by the shortage of natural gas, the announcement was celebrated by businessmen and politicians in the region, but above all by the Comision Federal de Electricidad (CFE).

The extension of the 2.6 Bcf/d Sur de Texas-Tuxpan marine pipeline will have a tremendously positive effect on the availability of natural gas in an area where Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex) has been the only supply option.

The $4.5 billion investment planned for this project, which will be developed jointly by TC Energía and the CFE, is about 45% of all the capital spent in the execution of the five-year gas pipeline plan of the previous administration. Therefore, in terms of natural gas, it is the most important project of the López Obrador government.

At 715 kilometers in length, with 1.3 Bcf/d of capacity, the gas pipeline that most resembles it is Phase 2 of the Ramones project. That pipeline system resolved the chronic problems of low pressure in the Bajío, and western Mexico. Undoubtedly, the extension of the marine pipeline will have a similar effect: imported gas will forcefully complement national supply in an area with natural gas balancing problems that date back decades. The Yucatán Peninsula will no longer be vulnerable to production fluctuations from Pemex processing centers and will no longer have to burn gas with high nitrogen content. Texas gas will be available to users in communities adjacent to the wonderful Mayan ruins of Chichen Itzá.

It’s also a victory in the sense that CFE is once again showing its willingness to work with the private sector. And it’s no exaggeration to say that this project will change southeast Mexico. But it’s worth questioning if this is the best way to do it. The economic information about this gas pipeline is very brief at the moment, but it is possible to make some rudimentary calculations. Each kilometer of this pipeline will cost $6.3 million on average – a value well above the $3.7 million/kilometer spent on the original marine pipeline from the South of Texas to Tuxpan in Campeche. The new pipeline would, at 36 inches, actually be smaller in diameter to the original, too.

In the first marine pipeline, the original five-year plan considered an investment of $3.1 billion as reasonable. A bidding process for this strategic pipeline yielded an even lower investment, at $2.9 billion. There was no bidding process for this pipeline. A strategic pipeline, either because it has a minimum diameter of 30 inches, a length of at least 100 kilometers, or because it provides redundancy to the system, or is a new supply route to a relevant market, must be tendered in accordance with the Hydrocarbons Law. So the pipeline contravenes the law.

Although the project is sponsored by the CFE, the system will benefit the operations of the other national champion in the energy sector, Pemex. The pipeline would make landfall at two points. In the first, in Coatzacoalcos, it will take gas to an area where Pemex requires gas for its refining and petrochemical production operations. Second, the pipeline will pass through Dos Bocas, the site of the current government’s most emblematic project, the Olmeca refinery. With this connection, the supply reliability of this facility is assured, and by 2025.

The complexity of the route and the multiple final uses foreseen for the transported gas make evident another deviation with respect to the law and the institutional design of the energy sector. The great absentee and displaced agent of gas logistics in the southeast is now the manager of the Sistrangas: Cenagas.

Cenagas had devised a plan to guarantee gas to the southeast. It revolved around the addition of compression stations to its system. These facilities would act in synchrony with the Cempoala compression station to boost the gas received in Montegrande, added to the production of Ixachi in the Playuela node. This plan would have cost $800 million. Even if the development of a project with such characteristics involved the replacement of pipeline sections in some areas, the amount of the replacements would never exceed $2 billion, given that the linear distance between Tuxpan and Cactus is approximately 1,000 km. In other words, the worst scenario for the modernization of the Sistrangas would not be as onerous as the extension of the marine pipeline in terms of cost.

At a time when the government’s discourse is focused around austerity, it’s surprising that the cheaper solution wasn’t opted for. Not only was a public bidding process evaded, but the government stopped listening to Cenagas. Today the old system that Cenagas operates has a net value of barely $350 million. With a much smaller investment, with direct employment impact in the communities of Veracruz and Tabasco, with the opportunity to help advance new production (that of Ixachi, Quesqui and other fields), a cheaper solution was there for the taking.

But this plan should have started more than two years ago if the objective of guaranteeing natural gas flow to Dos Bocas was to be achieved before 2025. Perhaps the government is aware of the extra price it is paying with Southeast Gateway, that this is the cost of ensuring the startup of the refinery without further delay. But by forgoing project allocation processes with incentives for efficiency, there is no way to affirm that the public interest is at the center of policy decisions.

There are other priorities and we will never know if another infrastructure company could have offered a cheaper gas transportation solution. TC Energia is within its rights to maximize its benefits, but CFE is obligated to minimize its costs. The agreement between CFE and TC Energía could also have a political interpretation. Perhaps the agreement serves as a sign that the private sector is welcome in Mexico. The López Obrador government seeks to send a message that it knows how to collaborate and join forces with North American companies. The process wasn’t transparent, didn’t follow the rules of competition, but the end result can be seen as positive. The project will transform the southeast. But it will also help transform the market from one of open access on paper to one in which the dominant intermediary will be the powerful and increasingly empowered CFE.

Prud’homme was central to the development of Cenagas, the nation’s natural gas pipeline operator, an entity formed in 2015 as part of the energy reform process. He began his career at national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), worked for 14 years at the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), rising to be chief economist, and from July 2015 through February served as the ISO chief officer for Cenagas, where he oversaw the technical, commercial and economic management of the nascent Natural Gas Integrated System (Sistrangas). Based in Mexico City, he is the head of Mexico energy consultancy Gadex.

"able to" - Google News

August 13, 2022 at 04:14AM

https://ift.tt/P6XKMJe

Column: Gateway Pipeline Shows CFE Willing, Able to Work with Private Sector - Natural Gas Intelligence

"able to" - Google News

https://ift.tt/tJu70RT

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Column: Gateway Pipeline Shows CFE Willing, Able to Work with Private Sector - Natural Gas Intelligence"

Post a Comment